If you stop to think about it, in today’s time and context, Rapunzel appears to be more of an Indian princess than a Western one. In the West the girls and women kept long hair for many centuries but it all stopped after World War 2. On the other hand, in India, that tradition is still alive and kicking. It therefore made sense to choose this particular story from numerous other options and adapt it to the Indian setting. For similar reasons, the south of India also appeared to be a more appropriate setting as compared to the north.

Extremely important. Stories carry great influence among readers, especially young ones. In today’s day and age, we need to have a princess who can serve as a role model. The old stereotype of a passive princess just waiting to be rescued simply does not work. I should add that her counterpart, the prince is also very far from the stereotypical prince. He is vulnerable and suffers from numerous ailments. That aspect too is important because it places an unnecessary burden on the young male reader. Why should the prince always be tall, strong and without any need for help? The story is also about the importance of partnership. The princess needs to help the prince before he can help her.

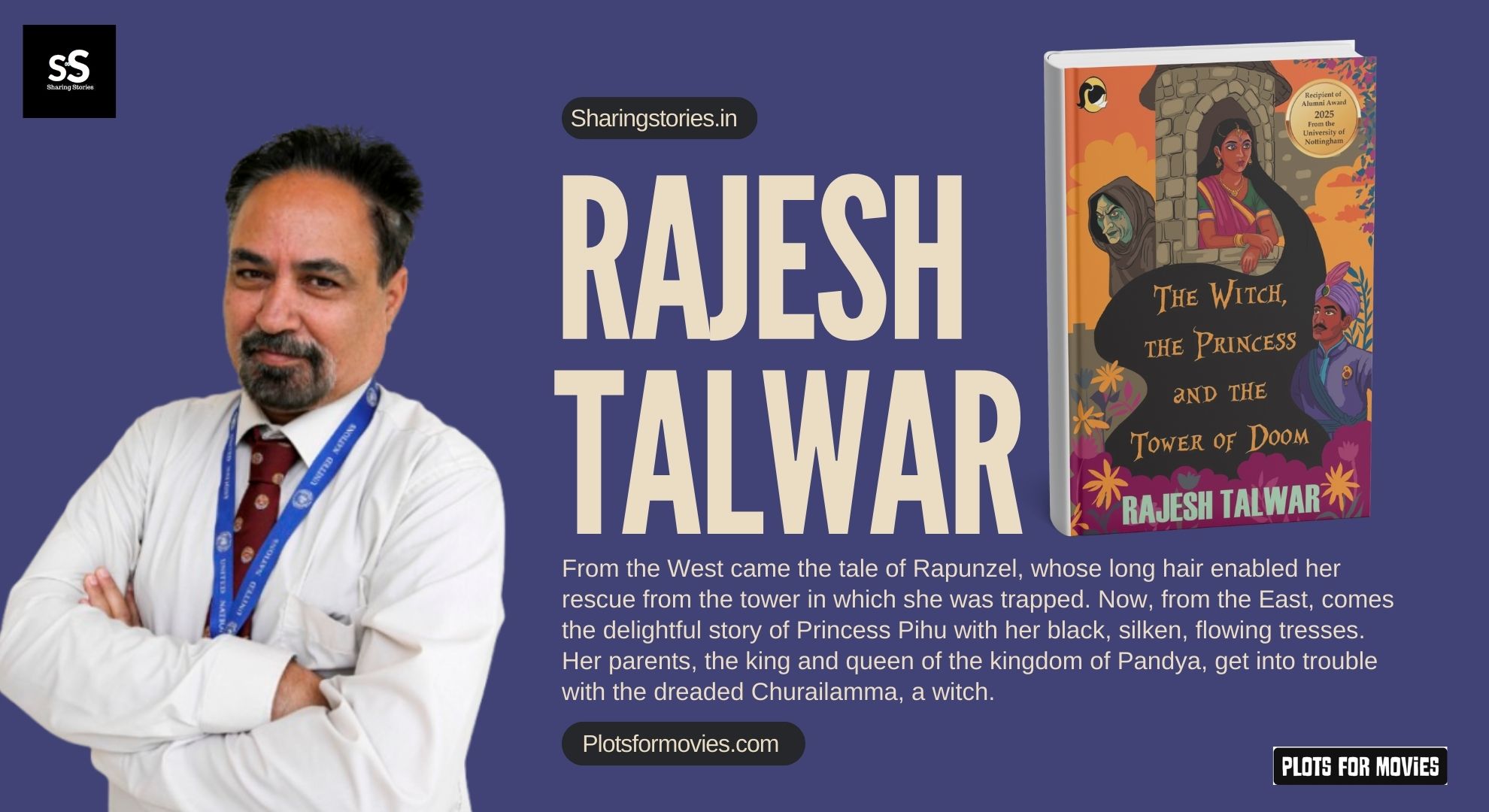

Young people today have acquired a more sophisticated intellect. You cannot, must not talk down to them. A cliched villain or vamp would be boring for a young reader aside from being less realistic or true to life. Now Churailamma is a very important character in the story, as you may have guessed. It could even be argued that she is the most important character, even more important than the princess and prince. There is a reason I have called the story ‘The Witch, the Princess and the Tower of Doom,’ and not, for instance, ‘The Princess, the Witch and the Tower of Doom.’

I believe that in the West too, they are in search of new exotic material. The blue-eyed, blonde princess is no longer such an engaging premise. An Indian setting would be far more interesting to not only a young Indian readership, but to readers from across the world. If you examine the situation, you will find that even Disney now makes movies that feature non-white characters such as in Mulan (1998) that had a Chinese main character or even Moana (2016) that had a Polynesian main character. I do believe that Indian stories for children, if marketed properly, have huge global potential, and, hopefully, the present one is no exception.

That is hugely important. After all you don’t want a child to be reminded of his school teacher while reading a story. As you suggest, lessons must not appear to be forcibly included. They should be gentle, unobtrusive. In general, I believe that Indian writers for children have to be especially careful, because we do often have a lot of unnecessary moralising in the country. The lessons must be organic to the tale itself, and not appear artificial.

I suppose that building the magical universe itself is the most challenging task. For me, writing the last segment of this book was specially challenging, where the reader discovers dimensions to the witch that s/he might not have suspected could possibly exist. Embedding the messages itself appeared organically. A gentle voice whispered in my ear as and when it was appropriate to do so.

For one thing it is definitely more enjoyable. You have to put yourself in a child’s position which is always refreshing. It also means getting rid of the cynical part of yourself, because your story must carry messages of hope, wonder and happiness. For some years now, I do try to write at least one children’s story every year. All writing is therapeutic but writing for children especially so, at least for me.

Truth telling for me is the most important responsibility of a writer. I tend to agree with JK Rowling that writing for children also involves truth telling, even in a work of fantasy. I think her original quote was something like: ‘I think the best children’s books are those that say something true.’

Need Publishing Assistance?